"On their deathbed, no one ever said they wished they had spent more time at the office." Bullshit.

"Living your best life" does not mean working as little as possible.

You have heard it, or read it, or perhaps even said it yourself.

“On their deathbed, no one ever said that they wished they had spent more time at the office.”

It is a ubiquitous phrase, used in living rooms and lecture halls around the world to articulate a feeling many of us share regarding our choices about how we spend our time. On social media, we are encouraged to “live our best lives” and not waste our time in service of work, unless it is to “get the bag” as quickly and easily as possible. This idea nearly always elicits assenting nods and encouraging emojis (“100!” “Thumbs up!” “Love!”).

But is it true? We submit that it is not, and that it can steer us wrong as we consider the very question it purports to answer.

First, a bit of background on the phrase: It was popularized by Paul Tongas, a US Senator from Massachusetts in the 1980s. Facing an uphill battle, he chose not to pursue reelection, and instead to spend more time with his family. By all accounts, this was the right decision for him at the time.

To his credit, Senator Tongas was asking himself the right question, though it is a question many would prefer to avoid. Bryan Johnson and a host of tech billionaires today are convinced that they will soon find the key to eternal life, which will allow them to put off this question forever. They are, of course, not the first people to dedicate themselves to this pursuit. The first written text in documented history, the epic of Gilgamesh, concerns the exact same goal that drives the current “longevity biohackers.” From the Ancient Greeks to the Arthurian knights to the Spanish explorers, the rich and powerful in every society have thought they were just one discovery away from avoiding death altogether.

But they are wrong. And they will lie on their deathbeds, looking back at their life and asking themselves: did I spend my brief, finite time on this planet in the right way?

It is a question every thoughtful person from every culture, in every age, has asked themselves. If they are wise, they ask themselves the question well before they get to their deathbed, in time to use the answer to make better decisions and maximize their time on earth.

Today, most people seem to be answering the question in a similar way: I want to “live my best life”: to drink wine with my friends and travel the world, and have relaxing spa days with beautiful views, and share it all on social media.

But, at our core, we know that this is not what life is about.

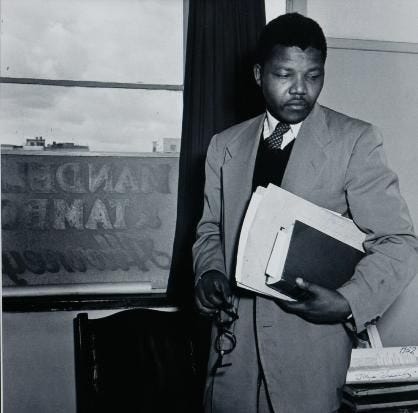

Nelson Mandela advised us to live differently. “There is no passion to be found playing small—in settling for a life that is less than the one you are capable of living,” he said.

Mandela’s life was not primarily about comfort or sensual pleasure or fun (though he did, famously, enjoy all three of these). Life was about accomplishing great things, about living the life he was capable of.

Did a dying Nelson Mandela regret the countless hours of hard work he put into freeing South Africa from apartheid? No, he did not. Did a dying Martin Luther King regret the long nights spent planning the sit ins and the boycotts and the marches that brought Civil Rights to America? No.

Accomplishing meaningful things requires hard work. That is reality. Anyone who succeeds in accomplishing something great accepts this fact early on in their journey. Take Mother Teresa. When asked why she moved from the comfort of England to the slums of Calcutta, she answered, “I wanted a hard life.”

Now, you might be thinking, “that’s okay for them, but not everyone is Nelson Mandela or Martin Luther King or Mother Teresa. We’re not all saving the world. Most of us are just normal people.”

True. But accomplishing something meaningful matters to normal people as well. I’ll give you an example.

My grandfather started a business fixing heaters and air conditioners out of his garage in 1941. Soon, he was drafted into World War II. He re-launched the business upon his return, this time with a young son (soon, three young sons) to provide for.

He knew no other way to succeed than through hard work. He started in his garage at dawn, worked straight until supper, and then did paperwork until bed. As in many family businesses, his wife became the accountant and controller as the business began to grow. My father recalls that the two of them immediately went to their home office after dinner every night to track invoices and balance the books until they slept.

My grandfather worked 7 days a week. On Christmas, after church and a brief gift-giving ritual, off he went to the “shop.” Easter, the shop. New Years, the shop. He took two days off in a row just once in 50 years—his wedding day, and a one-day honeymoon afterward. His third day of marriage, he was back to work.

My grandfather died when I was in college. I spoke with him in what we both knew were his last days. Did he regret that he spent all that time working? No. If he regretted anything, it was the fact that he could not keep my grandmother in comfort in her final days. He could not keep her from suffering multiple strokes, from developing dementia, going blind, losing her ability to walk and feed herself and bathe herself. If working even harder would have meant he could prevent those things, he would have gladly done so.

My grandfather was not ending apartheid or breaking Jim Crow. He sold kitchen equipment to IHOP franchises and built ice machines for the Holiday Inn. But the work was meaningful for him. It mattered, and he put in the work without complaint or regret.

It’s not true that hard working people, on their deathbed, always wish they had worked less hard. It’s also not true that people never wish they’d worked harder. Few people would say “I wish I’d spent more time at the office,” but many will say they wished they had accomplished something meaningful and lasting in their lives, and that they wish they had spent their time differently in order to have done so.

Now, to be clear, I am not saying that working more hours is uniformly better than working fewer. Many people achieve great things in relatively few hours. We have limited focus and energy, and that energy is often the limiting factor, not our number of hours worked. If Usain Bolt had spent more hours training and fewer hours resting and recovering, he is not likely to have run faster.

But I am saying that fewer hours or less work does not necessarily mean greater fulfillment. The question is not “how can I spend less time at work,” but “how can I make the time I do spend at work—and everywhere else--the most meaningful it can be?”

We all must consider this question for ourselves. But leaders are unique in that they have to think about it on behalf of other people, too. This is a huge responsibility, as well as a tremendous honor. Those of us in this position should take it very seriously.

Your employees, like all of us, have very little time on this planet. They are choosing to spend a meaningful amount of it with you, doing what you direct them to do, pursuing goals you set for them. Yes, you pay them to do so. But the money will not make these hours come back.

You have a responsibility to ensure that this time is not wasted. Set big, inspiring goals. Make them feel part of something meaningful. Create environments where they can thrive and reach their potential, where they can become greater than they knew they could be. Foster a sense of belonging. Show understanding and compassion and empathy.

When your employees are on their deathbeds, what will they say about their time with you? Will they regret spending too much time at the office? Will they be glad that they were able to get a paycheck with minimal effort so they could spend more time on the things that actually matter to them?

Or will they look back with pride and satisfaction at the teams they were on, the people they worked alongside, and the accomplishments they achieved? Perhaps they will say, “Yes, I worked very hard…but it was worth it.”

Thanks,

The Impactful Executive Team

PS - free free to share this newsletter with anyone that would find it useful.

Whenever You’re Ready, There Are 3 Ways We Can help You:

Find out more about TIE’s Top Team High Performance Program. Visit ImpactfulExec.com, read our 5-slide TIE teaser or 20-slide full TIE introduction.

Score your organizational health. Measure across our three levers, three levels, and nine elements using our 7-min Diagnostic assessment and emailed pdf report.

Improve your top team’s performance. Send us an email if you have further questions and schedule a 15-min triage call to see if we can help you.